Why you’ll want to read this

CAC is the first metric that every Marketer learns and is often painted as “Oh, it’s simply Customer Acquisition Cost”. But, over my career, I’ve measured CAC 15 different ways and every time I talk to a marketer about CAC they have a concern or question about it. CAC is so much more nuanced than people give it credit for.

How to properly define CAC

There’s a golden rule for metrics that they should be:

Easy to measure

Easy to understand

Easy to communicate

And while LinkedIn might convince you that CAC is a bad metric, there’s a reason it still matters. CAC nails the golden rule. It’s the cleanest way to see if your acquisition efforts are working and whether it’s efficient.

It’s also universally understood. Finance gets it. Growth gets it. Product gets it. That makes it a key internal metric. Externally, investors and shareholders expect it. Even if you use another methodology, they’ll still ask for CAC. That makes it a key external metric. Having a metric be both key internally and externally creates a level of stickiness that is hard to replace. So, CAC isn’t going anywhere anytime soon.

Throughout this article, I’ll show you where the traps are and how to make CAC work for you.

How to calculate CAC (properly)

CAC is a ratio, which means it has a numerator and a denominator. Obvious but we’re going to break apart each component and dig deeper into them.

The numerator: Marketing Spend

Marketing Spend can mean a lot of things and it can cover a lot of things. Everything from Paid Spend to headcount should eventually be included in Marketing Spend. Why eventually? Because I believe that the definition of Marketing Spend should evolve with the stage of the company.

Example

Take the example of a pre-seed founder. They’ve just read on LinkedIn that CAC should include all costs, from marketing to headcount. Their salary is $100,000. They run a $50 Meta test. If they include their salary, their CAC suddenly looks like $10,000. They don’t know their LTV yet, and now the number is telling them the business doesn’t work. That conclusion would be completely wrong.

So, how do you avoid this? The definition of Marketing Spend should align with the stage of the company and the goal of marketing at that stage.

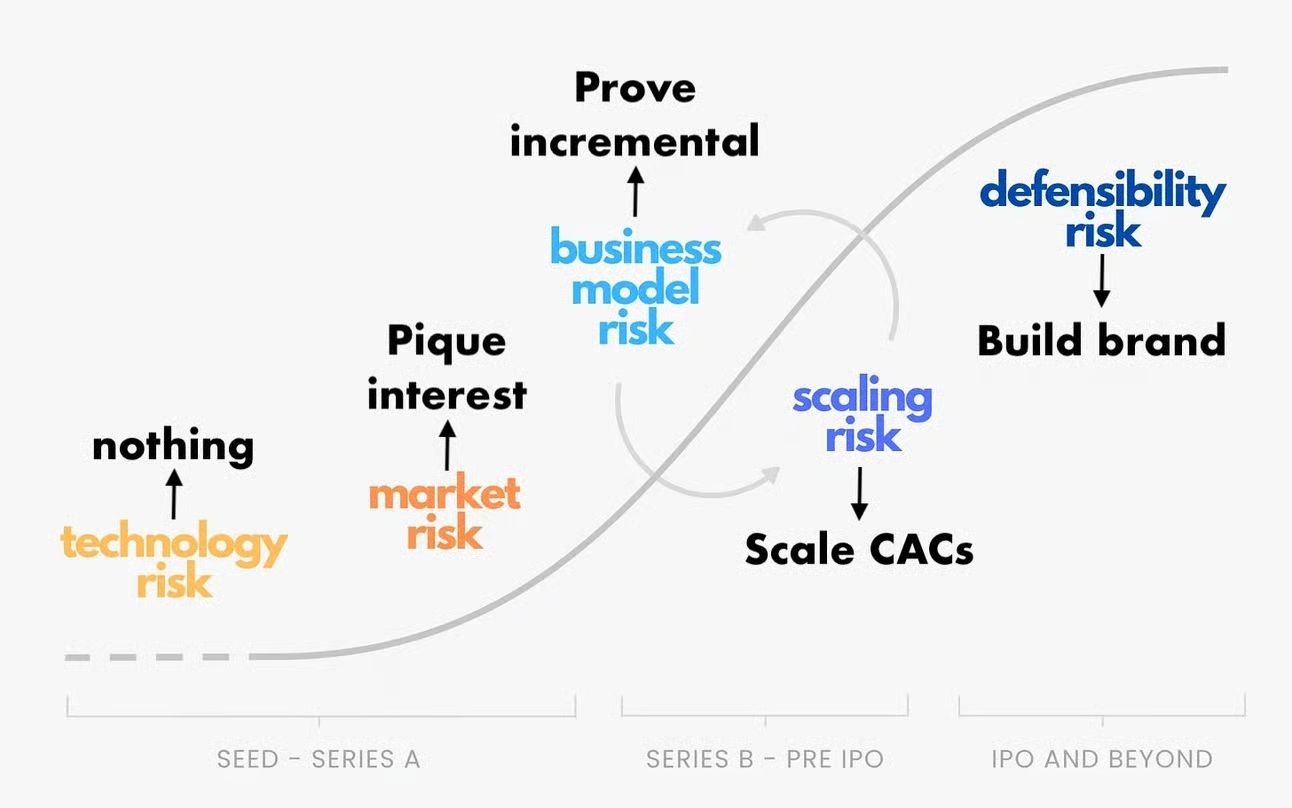

Stage 1

Stage 1 is about finding product-market fit. And the goal of Marketing is to see if it can find the target users. It’s not about efficiency. So, Marketing Spend should simply be defined as the money you’re putting directly into advertising.

Let’s say you estimate an LTV of $25 using hand wavey math. You run an experiment and the CAC comes in at $50. You can cut that in half over time through optimizations, a smoother funnel, and stronger brand awareness. But if your CAC is $10,000 just on marketing spend alone, the only way that makes sense is if you have a matching LTV, which is rare in consumer tech.

The point of this first stage is not precision. It’s to get a rough calculation that tells you if there’s a path to finding product market fit.

Trap

Most people know to include Paid Spend. This covers advertising on channels like Meta, Google, TikTok, or anywhere you’re paying for distribution. That part is straightforward.

But what about referral? If you give $10 to the referrer and $10 to the referee, that’s spend too. The same goes for affiliate payouts. You have to remember to include this. If money is directly going out the door to acquire a customer, it should be included in Paid Spend.

Stage 2

Stage 2 comes once you’ve found product-market fit and you’re starting to accelerate. Here the goal of Marketing is to find a repeatable motion. You’re still experimenting and testing, but you’ve got a decent foundation for the customer journey.

Here you should layer in costs that keep the engine in motion that aren’t tied to headcount.

Agency fees

Tools to automate campaigns.

Subscriptions to create and deploy ads

The idea here is to capture what it costs to keep the Paid Ads going.

Stage 3

Stage 3 is when you’re moving into scale-up mode. Here the goal of marketing is to create a sustainable acquisition engine.

You’ve got a repeatable GTM engine, product-market fit is no longer the question, and you’re comfortable with your monthly spend. At this stage, you’re likely to have one or two channels working well.

Now you want to account for MarTech costs and immediate headcount. These are the tools you need to support higher spend ( attribution or analytics ) and the people directly responsible for acquisition. That could be your marketing managers, an agency, or whoever is pulling the trigger.

The goal here is to understand if the acquisition team itself is profitable, or how close it is to profitability. You’re not optimizing for the entire company’s headcount, but you are for the immediate team running acquisition.

Stage 4

Stage 4 is where we get into the less defined territory. By now you’ve been in stage 3 for a few years. You’re a known brand in the space and you’re starting to invest in bigger teams and brand building. The goal of Marketing moves into creating a sustainable and global (or mass market) presence.

This is where you fold in costs like Data science and your broader performance marketing team. At this stage, CAC needs to reflect the full engine you’ve built around acquisition.

Stage 5

Stage 5 is when you’ve become a market leader. You’ve been around for a decade, your brand is established. The goal of Marketing is to create a sustainable and long lasting Brand.

Here you include everything in your CAC:

Brand & Performance Marketers

Marketing leadership

MarTech costs

Data science

What Marketing is trying to prove is that the entire Marketing engine is profitable.

When in doubt, lean conservative. The worst outcome is realizing too late that you’ve been undercounting your spend. This exercise is about balance: accounting accurately, motivating your team, and staying realistic about efficiency.

What about Brand Marketing Spend?

Brand Marketing Spend is one of the most controversial line items in a Marketing P&L. The natural tendency would be to include it in CAC right from the get-go, but that's not the right approach for two reasons:

Brand has a long-term impact

Brand impacts more than just customer acquisition

So, much like incorporating salary when calculating pre-seed CAC, you need to be careful about how you incorporate Brand Marketing spend in CAC.

The best way to navigate this is in 2 steps. First, treat Brand as an experimental budget where it doesn't impact your CAC. You want to prove that your Brand Marketing efforts can actually move the brand metrics that they're set out to do.

Then, once you have confidence in your Brand Marketing efforts, it's time to begin incorporating more scientific studies like incrementality tests and an MMM. Over time, you’ll want to incorporate Brand Marketing spend into CAC, but also ensure that you're benchmarking it to some sort of lifetime value or value metric. If we know Brand Marketing spend improves repeat rate, retention rate, average order value, and margins, then as long as your CAC is benchmarked to a lifetime value, it's okay to include Brand Marketing because that increase in CAC from including Brand Marketing will be offset by the value it's providing to the entire journey.

I estimate this to be in Stage 4 or Stage 5 for most companies.

So in summary, be careful when you include Brand Marketing spend in CAC, but if you're confident on its impact, then do include it because it adds more credibility to your team.

Hopefully you’re able to digest all of that because that was just the 1st part of CAC. Now, we get to the second part… the customers. Vamos!

The denominator: New Customers

The first question you should ask is “What is a New customer?” How do you define it? Is it a sign up? A visit? A first purchase? All of these are valid. My advice is:

Don’t use sign up. It’s too early

Acquisition should align with the start of LTV

Acquisition should be tied to your North Star metric

As an example I’ll use throughout, for Uber, the Northstar was rides per week. Acquisition was then defined as first trip.

Oh, but no so fast! There’s an added complexity we have to think about.

How do I connect the spend that I spent this week to the acquisitions that happened this week? You want the most accurate representative of the relationship between spend and acquisition (aka CAC).

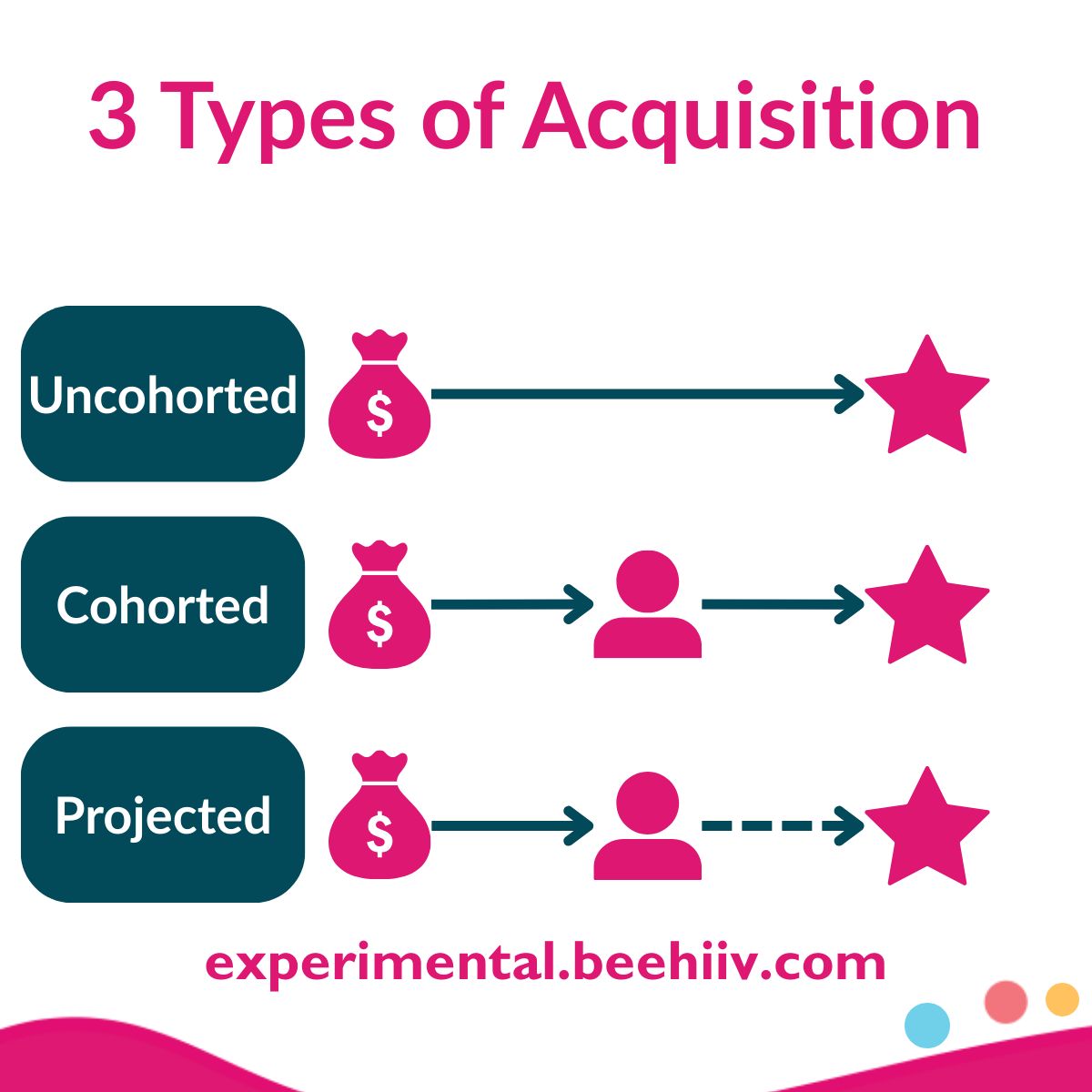

We’re going to explore 3 different types of relationships:

Uncohorted acquisition

Cohorted acquisition

Projected acquisition

Uncohorted acquisition

The definition is:

spend in time period ÷ acquisitions in time period

Uncohorted acquisition means you take a time period and look at all the spend in that time period and all the acquisitions and simply divide them. That’s your CAC. There is no defined relationship between spend and acquisitions.

In most consumer tech businesses, the signup-to-activation window is short so this works well enough. At Uber, 70–80% of new users who signed up also took their first trip that same day. In that case, the funnel from ad to conversion is fast which means your CAC is generally representative of the actual cost.

However, this assumes that most of the acquisitions are tied to the spend in that given time period, but it doesn’t have to be the case. This is the pitfall of this metric.

Cohorted acquisition

The definition is:

spend in time period ÷ acquisitions associated with signups in that time period.

Here, you tie the spend to the signups it generated, and then only count the activations that come from those signups. Revisiting Uber, if the signup happens in week 1 but the first trip happens in week 2, then those trips in week 2 impact the CAC of week 1.

Remember, we are cohorting based on signups so that you can align spend with signups. This creates a more realistic relationship between Spend → Customers.

The pitfall of this methodology is that it causes CAC to update over time, but it shouldn’t move THAT much because most of the relationship between signups and first activation should happen quickly.

Projected acquisition

The definition is:

spend in time period ÷ projected acquisitions of the signups from that time period

Here, you project the number of acquisitions that will be generated by that signup both in that same time period and in the future. For example (using Uber), signups happen today, some take a trip right away, and others take a trip next week. Instead of waiting, you project the acquisition rate based on known drop-off and retention patterns.

That lets you calculate both a projected CAC and a projected LTV aligned to the signup cohort. This is one of the benefits of this methodology is you accurately cohort spend to a signup and take advantage of data science to project.

The pitfall of this metric is you need to have the sophistication to do this and a robust testing mechanism to make sure your projected activations are actually happening.

So which method should you use? The answer depends on your consumer behavior.

If your activation happens quickly, uncohorted works well.

If you’re comfortable with numbers that evolve over time, cohorting can make sense too as it directly ties spend to signups.

If there’s a long gap between signup and activation, projected is often the better choice.

With this foundation in place, let’s move on to the next question that trips everyone up: which CAC are we actually talking about?

The various faces of CAC

How often have you heard the phrase “our CAC is too high”? The first question to ask is “Which CAC are we talking about?”

There are 3 major ones:

Blended CAC

Paid / Channel CAC

Marginal CAC

Incremental CAC

Blended CAC → Total spend ÷ total new customers

This is the classic version of CAC. Total marketing spend divided by total new customers. It’s simple, it’s clean, and it includes organic (which is theoretically free). That makes blended CAC look better than it really is. Still, it’s useful because you can quickly compare it to your average LTV. If the math doesn’t work, you’ve got a major problem.

For those of you already thinking “payback period is better,” I’ll come back to that in part 2. For now, LTV to CAC is still a solid ratio when it’s done right.

Paid / Channel CAC → Spend per channel ÷ customers from that channel

This is the one most people turn to after blended, and it’s the absolute worst. Channel CAC relies on attribution. Last click, first touch, multi-touch. It doesn’t matter. Attribution is always wrong. The only question is by how much.

Take Google Search. It often wins on last touch, which makes the channel look better than it really is. In-platform numbers will over-credit themselves, and even your own models can end up inflated. On the flip side, you might undercount, which is just as bad. Either way, channel CAC is the least reliable way to look at acquisition. DON’T DO IT.

Marginal CAC → Cost of acquiring the next customer

Marginal CAC gets you closer to smart decision-making. It asks: what does it cost to acquire the next customer?

Example:

January CAC = $10. You spent $100 and acquired 10 customers.

February CAC = $15. You spent $300 and acquired 20 customers.

On the surface, CAC in February looks like $15. But if you break it down: the first 10 customers cost $100, the next 10 customers cost $200. That means the marginal CAC for those additional 10 was $20.

Rule of thumb: keep pushing marginal CAC until it equals LTV. Beyond that, the spend stops making sense.

Incremental CAC → Cost of acquiring additional customers beyond baseline

Using the January example again: you spent $100 and acquired 10 customers. But what if you hadn’t spent anything? You might still have acquired 5 customers organically. That means the $100 only got you 5 incremental customers. $100 ÷ 5 = $20 incremental CAC.

Don’t confuse this with marginal CAC. The math might line up in this example, but they’re separate concepts and often don’t track together.

The same rule applies here: incremental CAC should be less than LTV. Otherwise, for every extra dollar you spend, you’ll never make it back.

Comparing the three, you’ll generally see:

Blended CAC is the lowest

Marginal CAC comes next

Incremental CAC is usually the highest

That’s because marginal CAC builds on blended, while incremental strips out any organic. If you’re not happy with your blended CAC, you’re definitely not going to like what you see when you calculate the others.

Wrapping up

CAC is here to stay. It’s simple to calculate, easy to explain, widely understood, and universal. But it’s also complex. If you don’t calculate it correctly, it works against you instead of for you.

Keep a few things in mind:

Define marketing spend based on the stage of your company.

Define acquisition based on your customer journey.

Always ask which CAC someone is referring to when they say “ours is too high.”

Blended, marginal, and incremental CAC are all valuable. Paid or channel CAC is not.

And that's it for Part 1. Here’s what you can expect in parts 2 and 3:

Part 2: Using CAC (application + strategy)

CAC as a decision-making tool

Benchmarking CAC

How to report on CAC

Alternatives to CAC

Part 3: Improving CAC (tactics + future-proofing)

Why CAC changes over time

CAC over the lifecycle

Levers to improve CAC

Was this article helpful?

Missed my last article?

Here it is: How to write a measurement brief