The Ultimate Guide to my Ultimate guides

As I look around for content in B2C Growth, I’m always left wanting more. Most of it feels like a tease but more accurately it’s an incomplete picture. It’s rarely enough to know enough about the topic and definitely not enough to action on it.

Its like I opened up a recipe to bake cookies and got the following:

Measure 150 g flour

Enjoy

So, I’m trying to change this by creating a series of Ultimate Guides. Yes, it’s a cliche name but it seems to stick so let’s roll with it.

My first one starts today with the Ultimate Guide to LTV. Over the next 4 weeks, I’m going deep on LTV and how to action it in 4 parts.

*For paid subscribers only

Let’s go!

How to calculate LTV

I want my… I want my… I want my LTV!

LTV is this mythical metric that everyone likes to bring up without any clue about how to calculate it, what it truly represents, and all the assumptions they’re making with it. It’s frustrating but more importantly dangerous. Everything from models to investments to venture funding is based on it so you owe it to yourself and your company to have a better understanding of it.

If there’s 2 things I want you to remember:

It’s never lifetime

LTV or Lifetime value is NEVER based on a lifetime. For reasons unknown to me lifetime value stuck , but it doesn’t make sense.

Align on what you mean by “value”

Value means a lot to many different parts of the organization. Value to whom is what we should be asking.

Now that I’ve asked you to throwout every part of the abbreviation, let’s build it up from scratch.

Defining Lifetime

Every LTV should be prefaced with some time value. Otherwise it’s incomplete. When you hear LTV, your brain should instantly jump to “How long we talkin bout here?!”

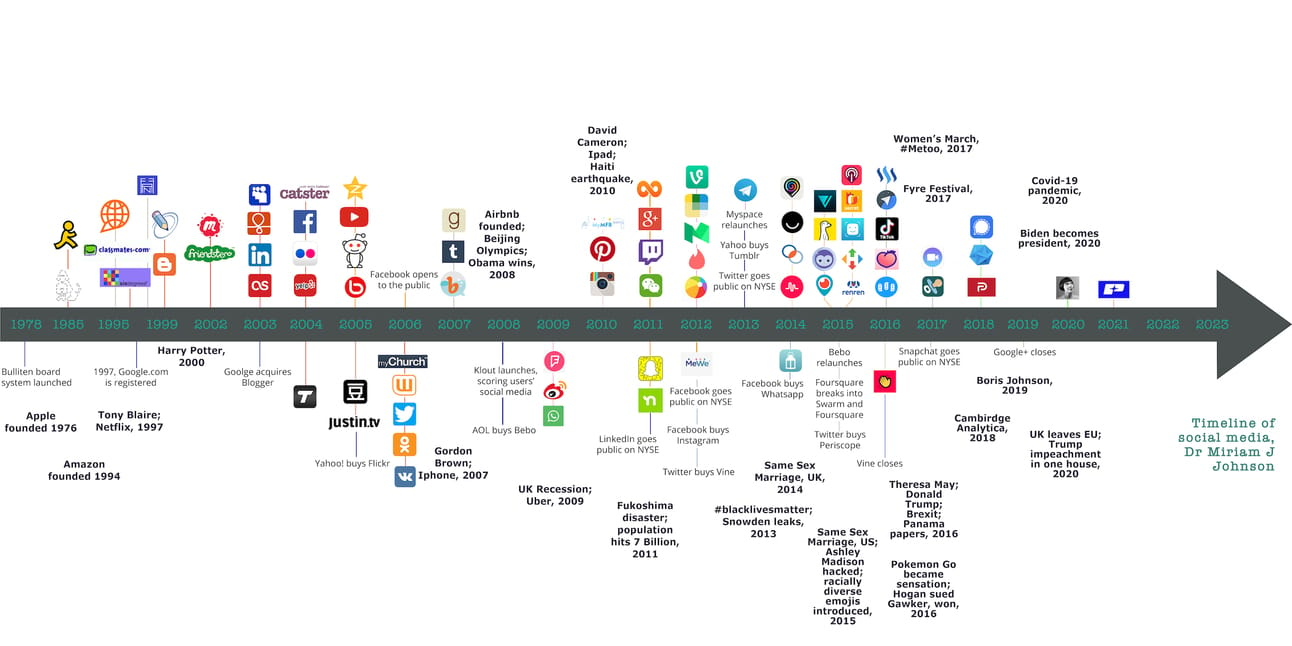

1 Year? 3 Year? 5 Year? more? In my career, I don’t think I’ve ever seen anything longer than 3 years and that makes complete sense in B2C Tech. I found this timeline on the webz and thought it was really cool.

Timeline of Social Media / Tech launches

It’s not the easiest to read but basically stuff is happening ALL the time and it truly disrupts what you’re doing. Imagine being Myspace only to see Facebook destroy you a few years later or any of the myriad of stories. Imagine your “LTV” model pre pandemic… looks reaaallly different I bet. The point is, you can’t predict more than a few years in the future so don’t try to.

So, pick a lifetime that reflects a mix of ambition and reality. If you’re a startup that just started yesterday, don’t even try and calculate LTV. If you’ve raised a Series A, maybe think about 6m - 1yr. Beyond that start to expand to 1-2yr and so on. LTV is a lagging indicator but when done right it can also be a rallying metric.

Defining Value

When we talk about value in LTV, it’s important that you understand there’s a giant asterisk there (LTV*). The V doesn’t stand for value. It stands for value to company (V2C) but LTV2C doesn’t sound as cool.

Anyone who is calculating LTV based on just revenue is simply shooting themselves in the foot.

Let’s go to an extreme example (because that’s where most models breakdown).

A customer buys a t-shirt on your website for $15

You pay $15 to the maker of the t-shirt and you keep $0

What is the LTV of this user? Is it $15 or $0?

The answer is $0. This person is worth absolutely $0 to the company. Companies that use revenue only in LTV will invest in the wrong efforts and will always runout of money.

What does all this mean?

LTV should be calculated using margin.

Now here’s where it gets super confusing and frustrating. Which margin do you use? I’ve looked at 10 articles at this point and some say contribution margin and some say gross margin. Fine, if that alone was the difference, but even the definition of contribution margin and gross margin can be different.

Do you feel like you understand either of those margins better? Probably not because I don’t. And there lies the problem. It’s never clear.

So what should you do?

The consensus answer is use contribution margin. However, if you use contribution margin as it’s defined you would be double counting variable Marketing costs. Instead, I’m going to be using a Modified Gross Margin or MGM.

The OG MGM

When in doubt, go more conservative and add costs but be careful to not over do it as you’re going to often compare yourself to less conservative benchmarks.

For most businesses, the MGM will be:

Revenue

- COGs (what you need to pay the person for doing that service / producing that item)

- Payment processing fees

- Support costs

- Distribution costs (server, shipping, etc.)

The only thing you shouldn’t subtract out are fixed costs like salaries, rent, tooling costs etc as well as variable Marketing costs. Anything else that is variable gets removed to find the Modified Gross Margin.

Putting it together

Now that we’ve defined lifetime and value, it’s time to put it all together. Here are the steps you should take to calculate LTV:

Calculate your variable costs as a % of revenue (except Marketing) → Do this for support costs, payment processing costs, hosting fees by looking at total costs over the past 6 months / revenue over the past 6 months. This will normalize it across products and geos while taking the most recent data.

Calculate cumulative revenue curves for X year from 1st transaction (you can also do it from signup if your product forces signup). What this means is calculate how much average revenue is created after the 1st transaction until X years per user.

Example: Average user spends $50 on first transaction and $25 in the next year. This then becomes a ratio of 1year revenue = 1.5x the first transaction.

The reason I recommend this approach is because your customers might be buying more from you over time so if you just used average AOV or even # of transactions then you’d undersell the value a customer brings.

Do the calculations on a cohort basis (details below) by week (or month) of 1st transaction

Cohort 1 | Cohort 2 | |

|---|---|---|

1st Transaction Week | Week 1 | Week 2 |

Cohort Size | 10 | 15 |

1st order AOV | 12 | 20 |

Cohort 1st order GMV | 120 | 300 |

Projected 1 year spend | 180 (120 × 1.5) | 450 (300 × 1.5) |

CAC | $2 | $10 |

Marketing Spend | $20 (2 × 10) | $150 (10×15) |

1 Year LTV | $180 - $90 COGS (50%) - $9 payment fees (5%) - $9 support (5%) - $4.5 hosting (2.5%) $76.5 | $450 - $225 COGS (50%) - $22.5 payment fees (5%) - $22.5 support (5%) - $11.25 hosting (2.5%) $168.75 |

1 Year LTV / CAC | $76.5 / $20 = 3.825 | $168.75 / $150 = 1.125 |

As you can see, cohort 1 is MUCH better for the business. I’m sure I could have fudged the numbers to make a less obvious example BUT the point is that breaking it down by cohort you have a better view of what’s happening than just a blended approach.

If you’re a marketplace, you have an added complexity which is to make sure you don’t double count when you’re calculating the LTV for demand side and supply side (which I highly recommend).

Here’s an example why:

A marketplace has 1 buyer and 1 seller. The buyer buys 1 item in the year for $100.

We can then calculate the 1year LTV for that 1 buyer using the formulas above. Now, what if we also want to calculate the LTV for 1 seller? Again, from the seller’s perspective , we include $100 in GMV and calculate a similar LTV as above.

Now the buyer spent $100 and the seller made $100 but we’ve now calculated it as if there’s $200 worth of revenue. So, we calculate a marketplace rate that let’s us distribute all the revenues and variable costs to simplify it.

To do this, make these adjustments:

Decide on a marketplace ratio to attribute to supply side and demand side. Per my friend Blake Hirt who is a marketplace expert, just keep it simple with 50%

Multiply revenue, COGS, payment fees, support, and all variable costs (excluding marketing costs) by this marketplace ratio

Calculate supply and demand specific CACs

Calculate LTV / CAC

Example

1 Demand Unit (Buyer, Rider, etc.) | 1 Supply Unit (Seller, Driver, etc.) | |

|---|---|---|

1 Year # of purchases | 18 | 45 |

1 Year AOV | $10 | $10 |

1 Year Revenue (GMV) | $180 | $450 |

CAC | $20 | $50 |

Variable Cost | - $90 COGS (50%) - $9 payment fees (5%) - $9 support (5%) - $4.5 hosting (2.5%) | - $225 COGS (50%) - $22.5 payment fees (5%) - $22.5 support (5%) - $11.25 hosting (2.5%) |

GMV * Marketplace Ratio (50%) | $90 | $225 |

Variable Cost * Marketplace Ratio (50%) | 56.25 | 140.62 |

1 Year LTV | $90 - 56.25 (Variable cost) LTV = 33.75 | $225 - 140.62 (Variable cost) LTV = 84.375 |

LTV / CAC | 1.6875 | 1.6875 |

It won’t always be the case that supply and demand LTV/CAC are the same. I actually think that’s just a crazy coincidence but by ensuring that you spilt shared variable costs (COGS, payment fees, support, hosting, etc.) and calculating specific CACs you’ll avoid double counting and over simplifying.

I know this is a bit of a doozy, so please reach out to me if you have any questions. I also want to thank Blake Hirt for all of his help in answering my numerous questions.

And that’s a wrap for part 1 of this Ultimate Guide to LTV.

Wrapping up

LTV can be such a valuable metric when calculated right, but it’s useful to remember 2 things:

It’s never lifetime. Always ask how long of an LTV are we talking about.

Ensure you’re using the right margins to calculate value. Contribution margin seems to be the preferred route but I prefer a Modified Gross Margin. When in doubt, go conservative.

If you’re a marketplace, calculate a supply vs demand metric so you can better understand those dynamics.

And, next time someone in your company throws around an LTV number in a meeting, ask them which margin they used. If they say “we don’t know” send then this article.

Until next time!

Enjoyed reading this?

Share with your colleagues or on your LinkedIn . It helps the newsletter tremendously and is much appreciated!

Missed my last article?

Here it is: How to run a killer Weekly Business Review